On Devirtualization

While meticulously photoshopping pictures of houses to remove the windows and doors, I realized that this act of cleaning, refining and smoothing that is fundamental to devirtualization.

Entry 01 in The Blind House essay series

by Jak Ritger

Above: "Blind House 01" - 2016, C-Print by Jak Ritger, Exhibited at Hammock Gallery, Provincetown, MA in 2020

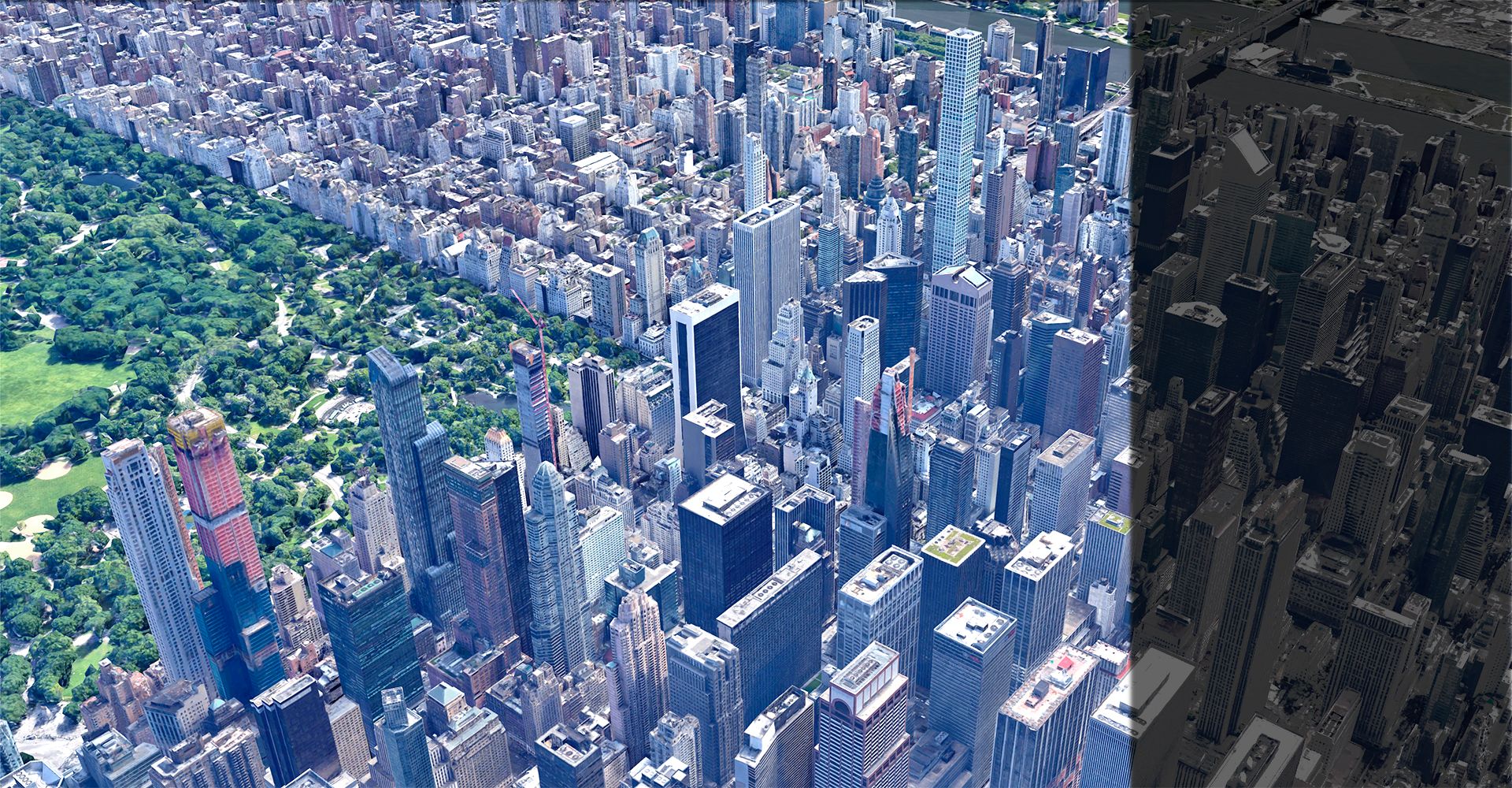

In 2014, I was living in my parent’s basement, racked with student loan debt and looking for freelance gigs on craigslist. When I travelled to NYC for interviews I would look up at the skyscrapers. Who lived there? Why were these buildings erected? How was there a shortage of affordable housing and new luxury high-rises going up simultaneously? Of course the simple answer is increasing inequality and runaway capitalism. But, what analysis could explain this development in more specific, current terms, and how could it fit into the framework of poststructuralism?

Jean Baudrillard’s concept of poststructuralism holds that meaning has become detached from practical value (usefulness or labor) and has instead taken on a “sign” value. This means that we buy specific goods because of a special aura that is created through marketing and advertising (instead of the goods’ explicit value as a product). As a result, rather than defining our world through a proximity of layered meanings (structuralism), we have begun to define our world through discreet signs and symbols or “simulacra.” In short: the virtual has colonized the real. I believe this to be an accurate assessment of life in the 21st and yet the production of luxury skyscrapers marches on with little or no change. If the practical value of these structures is overtaken by the sign value of their luxury, then who is the consumer? Increasing income inequality produces a smaller but wealthier upper class. How could this shrinking population of hyper wealthy support the massive developments of luxury housing?

The answer is that these domiciles were not and are not built for housing humans, but instead to house investments. In a practice known as “parking money” wealthy investors buy property in rapidly gentrifying or post-gentrified developing areas and then wait for the investment to accrue value before selling it off at a profit. The only humans to enter the luxury condos are a cleaning staff who come by to vacuum up dust from space and replenish flower displays for no one. The virtual system of corporate debt, stocks, and futures markets is extracted into private equity which then finds physicality in the interiors of skyscrapers. This realization changed the way I viewed the world. Once I started to notice this pattern of the virtual becoming physical I began to see it everywhere. I refer to this phenomenon of poststructuralism as devirtualization.

As I distilled this idea, I began working on a series of digitally altered photographs known as The Blind House series. My visual investigation into the homogenized architecture of the suburbs informed this distillation. While meticulously photoshopping pictures of houses to remove the windows and doors, I realized that this act of cleaning, refining and smoothing that is so fundamental to the advertising, fashion and design worlds is a key component of devirtualization. The virtuality of this perfection becomes the ideal state that we are chasing when we devirtualize. Or, to put it another way, we must alter ourselves and the world around us to match the perfection that we see onscreen.

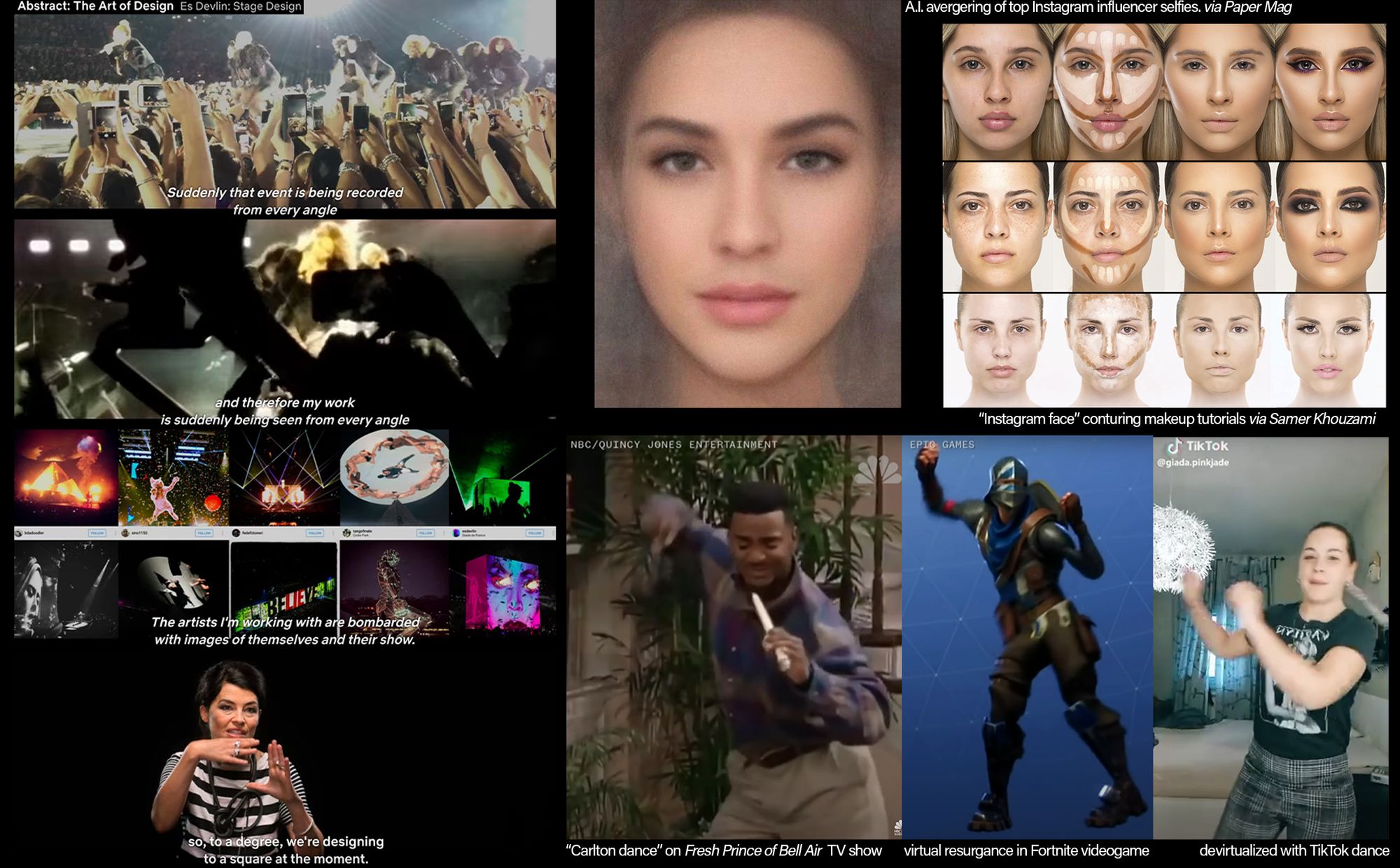

This dynamic coalesced in an article in the New Yorker titled “The Age of Instagram Face;” models, influencers and celebrities began altering their look through make-up, digital filters and plastic surgery in order to match a preferred aesthetic on the totalizing social media platform, Instagram. A homogenizing effect developed, were each individual began to look identical to each other in an arms-race for algorithmic preference. Stage designer, Es Devlin, reports a similar development in her practice, were the music performance spaces she builds must “look good on Instagram” i.e. compositions must fit into the square video captured by concertgoers. In the fine-art world a parallel development takes hold in what is now somewhat derisively referred to as “post-internet art,” or the pressure to create good looking installations that serve as backdrops for selfies. Away goes the dark spot lighting on the work, in comes the flood lights, ensuring any photo taken from any angle looks flattering. The virtual smartphone camera and the virtual crowd on the other side of the screen now determines the physicality of real space. These devirtualized gallery shows display artwork that fits into the same schema as luxury high-rises: not created for human posterity or enjoyment, but as a speculative commodity to be packed away in a tax-haven freeport accruing investment value.

Even virtual spaces have become devirtualized. As TikTok becomes a centralized digital forum for Generation Z, other older media forms have contorted themselves to fit into the dynamics of the platform. TMS pop music writing trio designs songs to “do something weird that works on TikTok”. The concept of the song should be simple enough to translate into a digital karaoke sing-along and also provide a a sense of vulnerability and honesty that can fit into intimate frame of a selfie video. Music videos serve as visual seeds for TikTok, providing a professional choreography to copy. Conversely, TikTok dances act as a devirtualization in other instances, such as recreating dance moves from victory displays in the Fortnite video game that were in turn lifted from the Fresh Prince of Bell Air. Whereas dance and choreography express emotion and create something unique and fleeting, TikTok dance creates permanent loop centered around “knowing the moves” and presenting homogenous roboticness. This is a key development of devirtualization, the original potential of a certain form: such as dance, art, stage design, or architecture is removed and replaced with smoother, frictionless intent. This signal-focused version is molded into a shape that is suited for platforms driven by algorithmic gods or our virtual system of debt and investment.

This negation of potentialities through devirtualization is perhaps most apparent through the evolution of skatepark design. Skateboarding combusted out of a multi-year drought in southern California. No good waves to surf plus empty swimming pools and drainage ditches pushed surfers to fashion surfboards for the street out of dresser drawers and roller-skate trucks. The new sport then moved from the suburban landscape to the city with its plaza stair sets to jump, curbs to grind, and corporate angled architecture to carve. Skatepark design created a virtual space that copied these designs 1 to 1, even down to the tile coping from swimming pools or faux brick pyramids from NYC FiDi office buildings. From there, skatepark design exploded into gorgeous flowing embankments, benches that grow out of the ground, and pathways to move throughout the park in order to create continuous skate trick runs known as “lines.” The proliferation and popularity of skateparks, first created under bridges by D.I.Y. skaters reclaiming underutilized real estate for public use, catalyzed the growth of “pre-fab” parks. Beyond this urban designers have injected the aesthetic of the skatepark into the zeitgeist; the parks are a symbol of a proactive recreation-oriented city plan. This aesthetic has now found its way back into corporate office design, public parks, and “place making” constructions. The key difference between the virtual space of skateboarding parks and devirtualized skatepark inspired spaces is the usage of a hostile architecture tactic known as “skatestoppers”. These small metal knobs restrict a bench’s utility for skateboarding tricks. “Skatestoppers” can also take the form of gaps in pavement or bricks that make it difficult to skate over. In this instance, the post-gentrified landscape devirtualizes skate design, negating the politics of exploration, experimentation, and expression, reducing it down into simple aesthetic.

In the next edition of The Blind House essay series we will look at Baudrillard’s critique of “Hyperreality” or the overproduction of reality, and how devirtualization has become a byproduct of surveillance capitalist structures promoting hyperreality at scale.