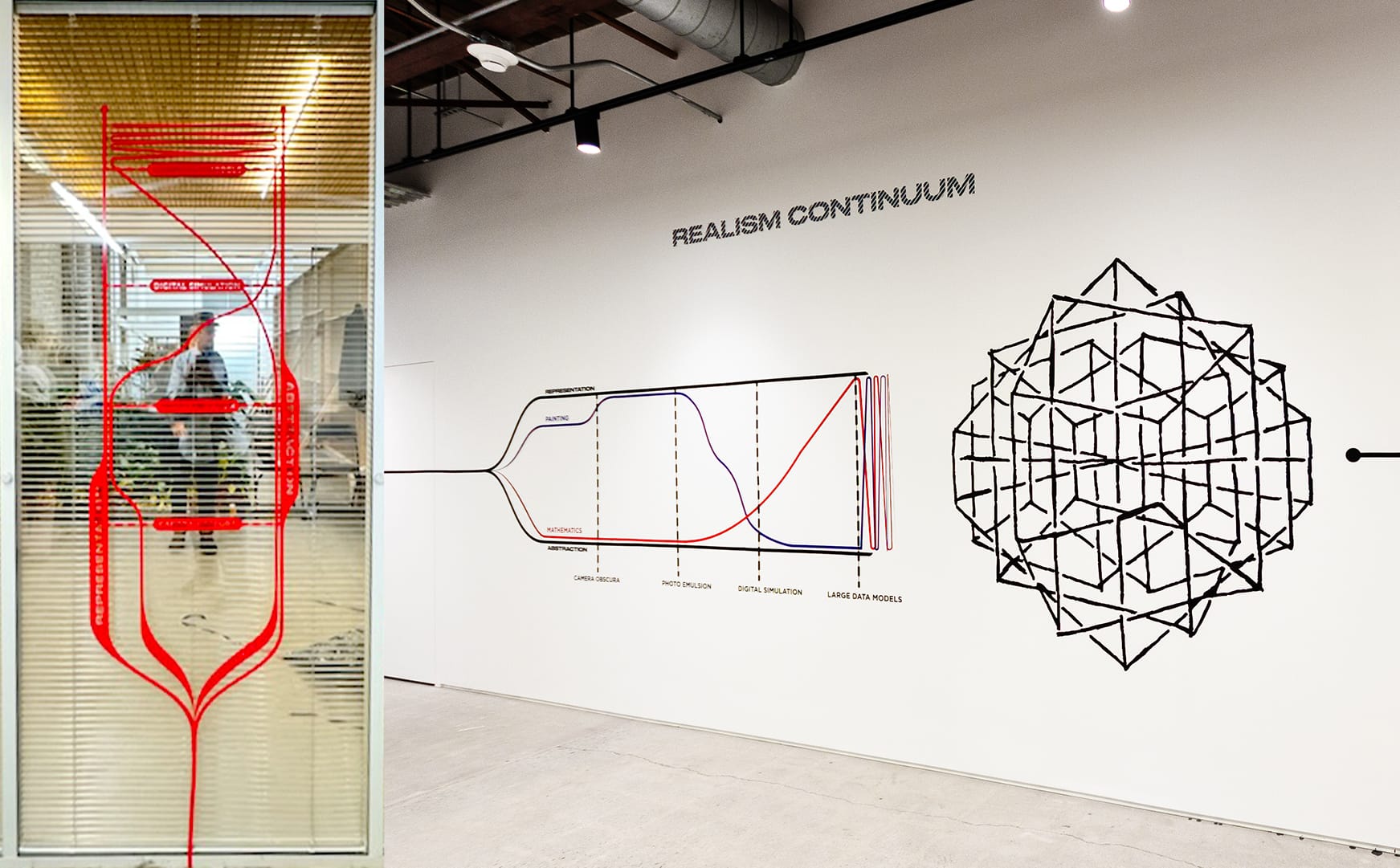

Realism Continuum

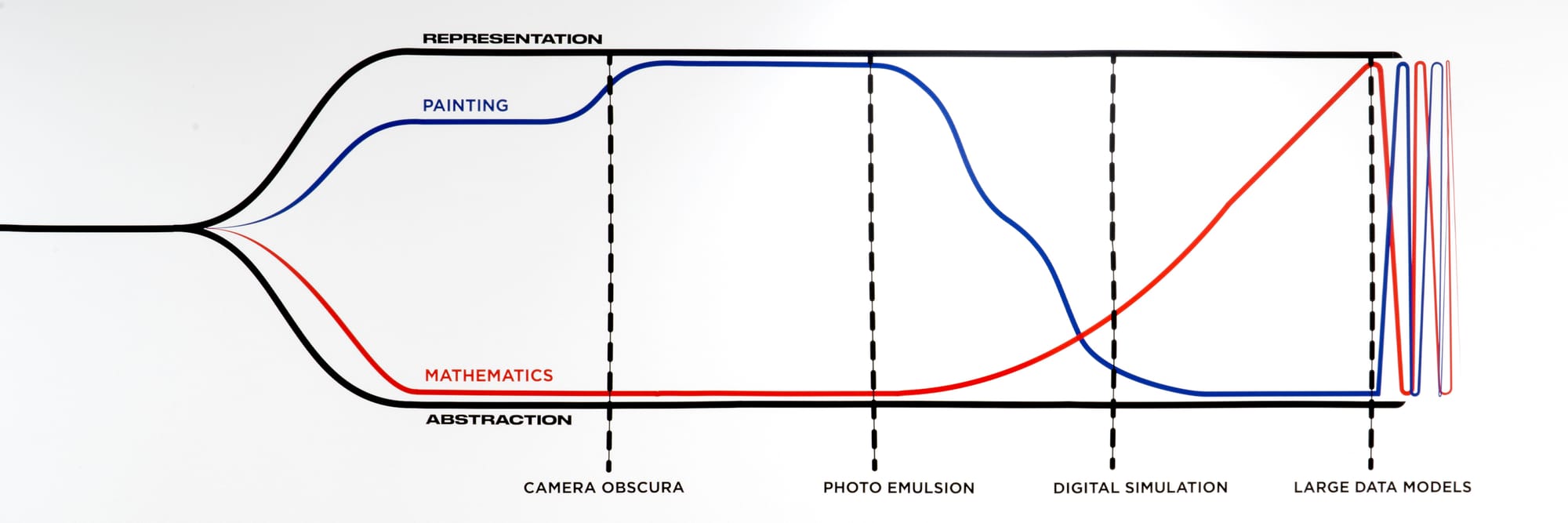

An attempt at plotting the history of painting and mathematics in relation to the technologies of capture in a one unified model.

by Jak Ritger

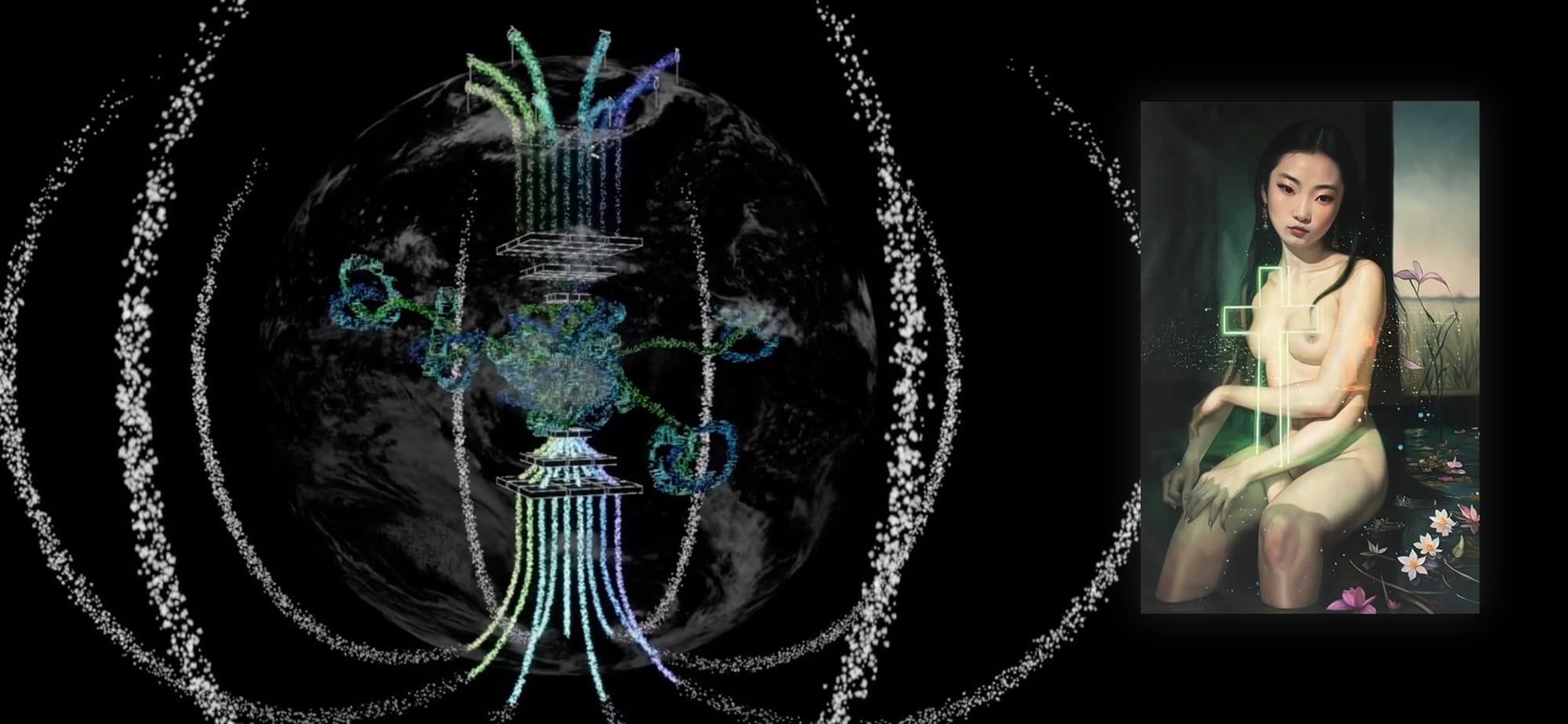

This summer, I was invited to create a series of vinyl wall installations for an exhibition dealing with higher dimensional thinking at Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art. As part of "Another Dimension" a camera obscura was created inside the museum by FR MoCA. I was captivated by the magical effect of the ancient yet futuristic images cast upside-down and backwards on the projection screen. I started digging back into David Hockney's research around camera obscura and began seeing similar reflexive patterns to developments of machine learning. I set about updating Hockney's trend-lines and adding a second vector to describe the evolution of computation. The result is a provocation to encourage inquiry, not the final word on the matter. The following are collected thoughts and explanations as to what I am trying to describe.

This model advances through time in a rightward direction, splitting from a unity of form into two modalities for making sense of the world: Abstraction and Representation.

As the timeline splits, the mathematics trend line sinks into abstraction consistently. Math is always a simulacra of world. Successful engineering takes a mathematical model and adjusts it based on ground-truth. Sometimes the thermodynamics just don’t work out the way that you think. We use numbers as a placeholder for what is outside the window. Meanwhile, painting is riding high on representation. Here I am focused on the western painting tradition, which is of course an already limited purview into the discipline. In the pre-renaissance period, painters were chiefly concerned with depicting biblical scenes. Representation was mandatory as it was dangerous if art was interpreted as serving something other than God.

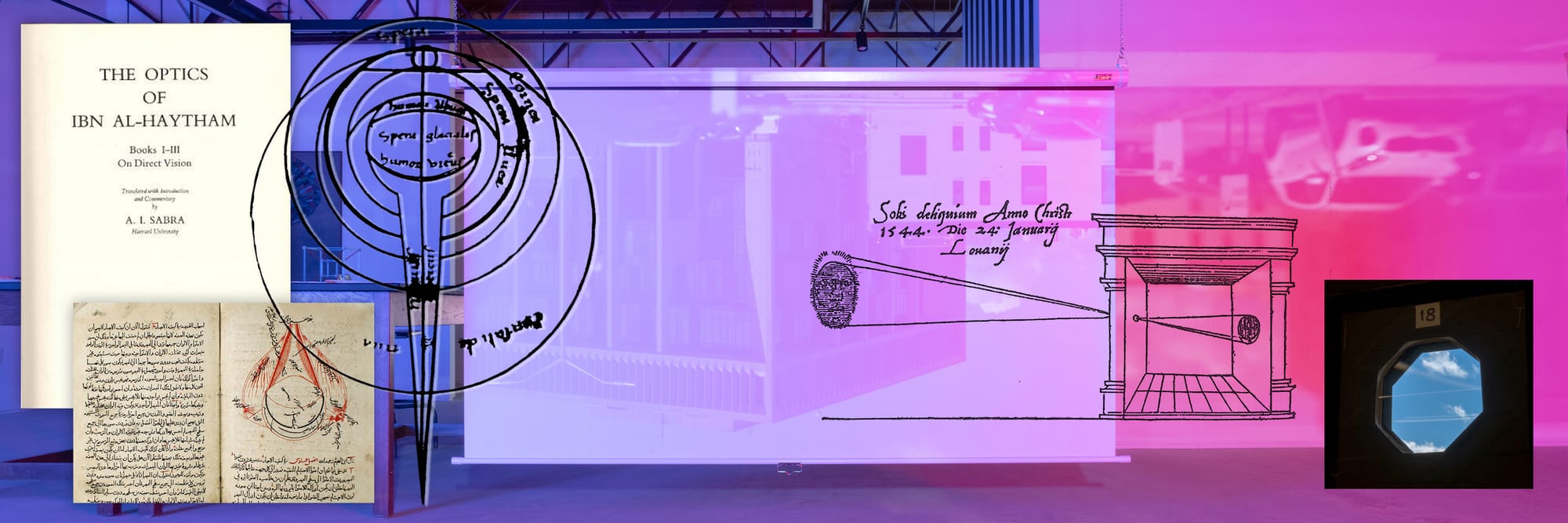

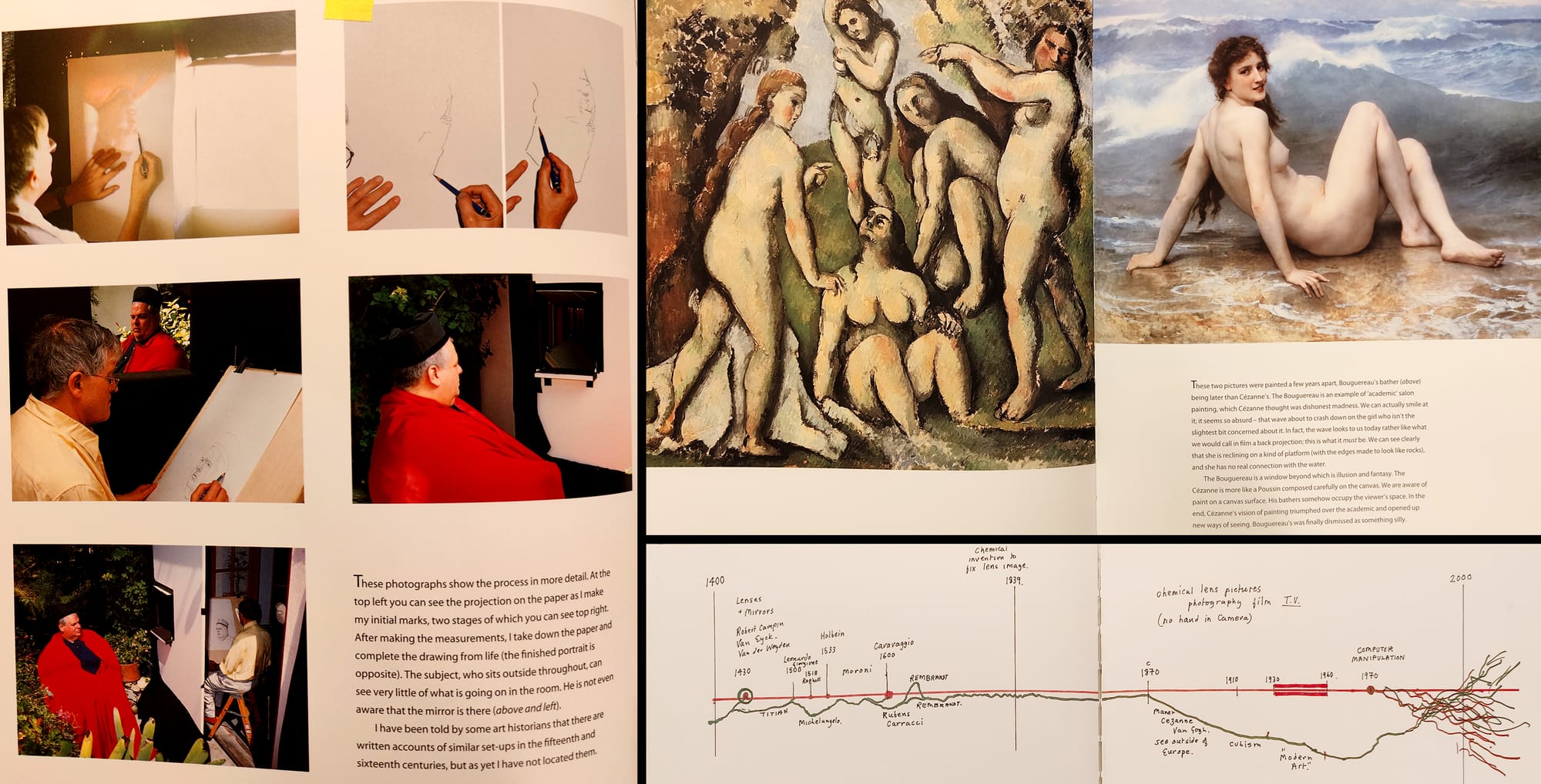

An Arabic mathematician and astronomer, Ibn al-Haytham first described the camera obscura in 1051, but it would take another 500 years for the knowledge to make its way to Renaissance Europe. This new optical tool provided a live projection of the subject onto the canvas. As a result, the red painting trend line pitches up closer towards realistic representation. A portrait sitter's expression and unique features could be captured in quick traced lines, rather than the monotone blankness required for consistency across many hourlong sessions of sitters without optical aids. But, as described by David Hockney in his research, "Secret Knowledge", this ease of capture and representation metabolized into a boring, overwrought academic style. Against this monocultural stagnation came waves of rebounding abstraction with impressionists such as Paul Cézanne leading the charge.

The advent of photo emulsion in the 1800s brought more upheaval to the tradition of painting. The medium of paint on canvas was no longer the standard for capturing one’s likeness. At the same time, every image captured by exposing a treated plate to light was hopelessly bound to our earthly realm. Painting was freed to explore the upper bounds of experience, that which is beyond words. Abstract painting was kicked into overdrive, with mid-century Large Abstract Paintings becoming the standard. Again, what had started as a stylistic revolution metabolized into a safe formula endlessly repeated.

With the introduction of photography, mathematics was given the first glimpses of representation. The tools of capture became surveillant and started to derive behavioral outcomes rather than simply capturing what was in front of the lens. As photographic documentation and experimental refinement increased in complexity, the domain of mathematical modeling evolved into digital simulation. The operators of computation were given the ability to see into patterns heretofore hidden. As we began to sense the invisible, our reality became thicker and rich with data.

Simulations of world snowballed together into larger and larger networks of networks and large data models came online. Weather predictions became more accurate and we sensed the effects of anthropogenic climate collapse. With this epistemological shift came another realization: as mathematics approaches representation with one-to-one models of world we no longer have the ability to audit or understand the algorithmic apparatus that is generating and adjusting the model. The viewfinder of the camera starts to become blackbox just as the whole earth comes into view. And so, we find ourselves ricocheting between the representation of detailed models and the abstraction blackbox machine learning.

At the same time, painting has also become a medium caught in this hyperreal ricochet. The introduction of AI-generated images has thrown the entire practice of paint on canvas into upheaval. The new aesthetic tendencies require us to look closer at the painted form: is it made by hand? or did a computer controlled arm direct the brush? is it really painted or is this machine-generated imagery printed onto a canvas? The aesthetic of AI images combine the painted image with photographic and CGI sources to create an amalgamation of all visual material. Nevertheless, painted wall works remain the chief vessel for contemporary art’s circulation and reproduction through the market. The painting itself is not simply a portrait of a sitter or still life, but a conceptual work rooted in the artists relationship to the picture. In this way, the practice of painting can no longer simply be representational or abstract. It is forced to exist as something else entirely and so the ricocheting persists.